Want to get your pay sooner?

We’ll ask just a few questions to see if Chime® can help you unlock your pay early.

It shouldn’t take more than a minute.

Do you want the ability to access your pay on your schedule with no mandatory fees?

When do you get paid?

Would accessing up to $500^ before your payday be beneficial?

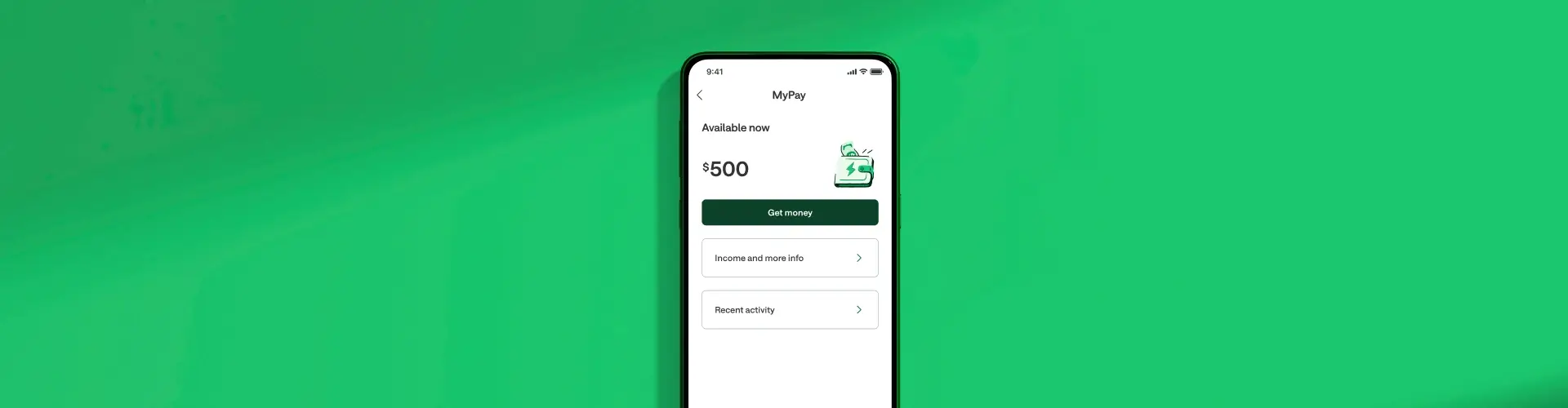

It seems like Chime MyPay is right for you.

- MyPay lets you get your pay when you want, up to $500^ before payday.

- No interest*

- No credit check

- No mandatory fees

^ To be eligible for MyPay, you must receive Qualifying MyPay Direct Deposits to your Chime Checking Account as set forth in the MyPay Agreement. A Qualifying MyPay Direct Deposit is a deposit from an employer, payroll provider, gig economy payer, government benefits payer, or other permitted source of income by Automated Clearing House (“ACH”) or Original Credit Transaction (“OCT”). Your MyPay Credit Limit and Available Advance Amount may change at any time. MyPay is a line of credit and available limits are based on estimated income and risk-based criteria. Eligible members may be offered a $20 – $500 Credit Limit per pay period. Your Credit Limit and Maximum Available Advance will be displayed to you within the Chime app. MyPay is currently only available to eligible Chime members in certain states. Other restrictions may apply. See Bancorp MyPay Agreement or Stride MyPay Agreement for details.

* Option to get funds instantly for $2 per advance or get funds for free within 24 hours. See Bancorp MyPay Agreement or Stride MyPay Agreement for details.

Explore our Blog

Popular Blog Posts

Want to get your pay sooner?

We’ll ask just a few questions to see if Chime® can help you unlock your pay early.

It shouldn’t take more than a minute.

Do you want the ability to access your pay on your schedule with no mandatory fees?

When do you get paid?

Would accessing up to $500^ before your payday be beneficial?

It seems like Chime MyPay is right for you.

- MyPay lets you get your pay when you want, up to $500^ before payday.

- No interest*

- No credit check

- No mandatory fees

^ To be eligible for MyPay, you must receive Qualifying MyPay Direct Deposits to your Chime Checking Account as set forth in the MyPay Agreement. A Qualifying MyPay Direct Deposit is a deposit from an employer, payroll provider, gig economy payer, government benefits payer, or other permitted source of income by Automated Clearing House (“ACH”) or Original Credit Transaction (“OCT”). Your MyPay Credit Limit and Available Advance Amount may change at any time. MyPay is a line of credit and available limits are based on estimated income and risk-based criteria. Eligible members may be offered a $20 – $500 Credit Limit per pay period. Your Credit Limit and Maximum Available Advance will be displayed to you within the Chime app. MyPay is currently only available to eligible Chime members in certain states. Other restrictions may apply. See Bancorp MyPay Agreement or Stride MyPay Agreement for details.

* Option to get funds instantly for $2 per advance or get funds for free within 24 hours. See Bancorp MyPay Agreement or Stride MyPay Agreement for details.

Log in

Log in